Fifteen years ago, new mom Jen Vogus – now a parishioner at Holy Family Church in Brentwood – became concerned about her five-week-old son. “Aidan was a full-term baby,” said Vogus. “I had a normal birth. But shortly after he was born – Mother’s Day, 2002 – I was breastfeeding him and he started doing this eye twitch and lip pucker thing. It was odd, and I had never seen it before.”

The family’s pediatrician confirmed that Aidan was having seizures. “It was devastating,” recalled Vogus. “And neither of us – Tim (Jen’s husband) nor I – were familiar with anything to do with seizures.”

Like footprints washed away

It would be a quick and extensive education. But learning what was causing Aidan to have seizures would take years to discover and significant advances in diagnostic technology. The missing piece was that Aidan’s seizures were due to a novel chromosomal deletion, called STXBP1.

Initially, Aidan was treated with phenobarbital, which appeared to arrest the seizure activity for about a year. Then it came to light that Aidan had been having seizures in his sleep, and most likely for quite some time. These nighttime attacks greatly affected his sleep schedule; he’d be up at night and exhausted during the day, which was trying on the whole family. “Not being able to help your child, that was the hardest thing,” Vogus said. “You feel like there’s nothing you can do, and you just have to wait it out.”

The seizures would continue, unabated, throughout Aidan’s young life, every day, multiple times a day. That constant invasive activity would take its toll on Aidan’s physical, neurological and cognitive development. “A doctor once explained it this way: seizures are like footprints in the sand,” said Vogus. “During the day you make all these footprints and you learn all this new stuff and then the tide comes in – the seizure comes in – and just washes it away.”

The older Aidan got, the more delayed he became compared to typically-developing peers. He consistently missed milestones, like crawling, walking, and especially talking. To this day, Aidan is almost completely non-verbal, primarily due to his physical challenges. Vogus is convinced her son has a lot to say, because his receptive language is much better than his expressive. He simply isn’t able to put together the fine motor movements to create speech.

It wasn’t for lack of trying. The family did “everything, for years and years” according to Vogus, which, beyond extensive testing and doctor visits, included an exhausting weekly schedule of speech, occupational and physical therapies, first privately and then through the school system. He took more than 20 different medications, proven and experimental, with extremely challenging side effects. This frustrating trial by error process left Vogus feeling like Aidan was a “guinea pig”, and that she was complicit in that treatment.

Guilt wasn’t the only emotion. “My perceived inability to help my son left me feeling inadequate and isolated,” Vogus said. “My husband is very involved, loving, and supportive and by no means have I been alone in this journey. But as his mom I felt responsible for all that Aidan had to endure, and that it was up to me to find a ‘fix’.”

Add to those feelings a constant anxiety about what Aidan’s future would bring. When he entered elementary school, it became increasingly difficult for his mom to not compare him to other students. The gap in abilities grew wider as the list of activities he could participate in got shorter. And, because of his communication limitations, it was nearly impossible for his teachers to understand him or to figure out what he liked or didn’t like. They were certainly not witnessing the positive attributes that his mom saw in him, nor the preferred activities he was engaged in.

“Even if I would drop him off in the morning and tell an aide, ‘this is what Aidan did this weekend,’ it kind of got lost throughout the day,” said Vogus. “Which is understandable.”

A picture = 1,000 words

So Vogus tried to think of a method to communicate this information in a more permanent and visual way. She landed on taking photographs of Aidan involved in his favorite pastimes. She sent the pictures with captions to school with Aidan on Monday mornings for him to show his teachers and peers.

“It gave him a voice to share his interests and all that he was capable of doing,” explained Vogus. “Teachers and other students were delighted to learn that Spiderman is his favorite superhero; that he takes riding lessons on a white horse named Lady; that he can hold his breath and swim down to the bottom of the pool; that he loves the thrill of the wildest rollercoasters; and that he gives his dad the biggest bear hugs of all.”

Aidan’s peers would acknowledge that they enjoyed some of those pursuits as well. That feedback helped Vogus realize that Aidan was more like other kids than different. Adults in Aidan’s life – besides his mom and dad – began seeing Aidan in a new light too. “Taking photos that made me grateful for Aidan was also a catalyst for him to build more lasting and meaningful connections and interactions with peers who became his friends, and teachers and other adults in his life,” said Vogus.

A two-way communication system

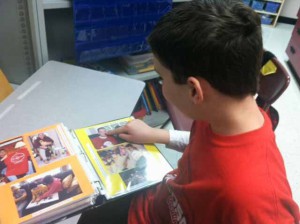

The photography venture soon evolved into a two-way communication system. Vogus organized the pictures into a book, which in turn inspired others to contribute to it. Aidan’s teachers and aides at school began taking their own photographs of Aidan immersed in school happenings to share with Jen and Tim at home. “Pretty soon his photo book took on a life of its own,” said Vogus. “Aidan helped type the captions, glued the photos into the book, and shared his visual stories with everyone. He’s been keeping a photo book of life at home and school since the second grade and now he’ll be a freshman in high school!”

Vogus looks back through the filled books from time to time, just like Aidan does. She calls them her “Gratitude Journals”. They make her thankful for the good life they have, thankful that Aidan has had a way to share all that he enjoys, and thankful that others have come to appreciate and love Aidan nearly as much as she does.

The everyday things

There’s another thing to be thankful for. Aidan has been, miraculously, seizure-free for seven months, thanks to a special oil – Cannabidiol, or CBD for short – that’s derived from the marijuana plant. This new option came to Tim and Jen’s attention after a CNN special by Dr. Sanjay Gupta. The Vogus family advocated with their elected representatives for the Tennessee General Assembly to allow families with this particular gene disorder to purchase the oil from out of state, when a more general medical marijuana bill had failed. The CBD bill was signed by Governor Haslam in May 2015.

But that’s a long story for another day. In the meantime, Vogus is happy to count her blessings. “The biggest thing that Aidan has taught me is to really be present, and to appreciate the little things in life,” she said. “That’s what I try to capture with my photographs of him: the everyday things. When you look back on a life, it’s the everyday things that matter.”

This article first appeared in the Tennessee Register.

Speak Your Mind